Crosskey Does Donation Creation

When you wake up in the morning, what drives you? What makes you sit up, stretch, and embrace the day? At Crosskey Architects, why we wake up energized and eager to get to work is quite clear – to inspire others, transform communities, and have some fun doing it.

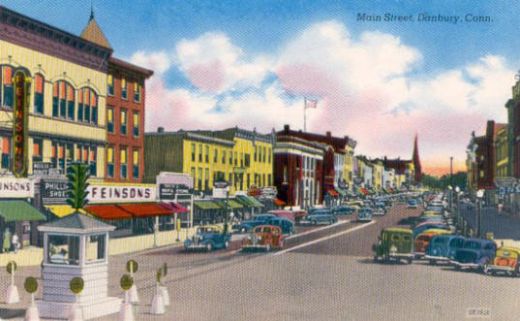

The Role of Developers in Preserving Main Streets

The old adage, everything old is new again, holds true in most facets of everyday life. Styles of clothing change reincarnated in different forms, the bold neon colors of the 1980s have reemerged in current athletic wear. Movies are no longer original ideas, but rather remakes of past hits; in 2014 alone, new renditions of RoboCop, Annie, Godzilla, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, among others, appeared in theaters. Old buildings, particularly in downtown business districts, are being rediscovered as an alternative to new construction. This trend is fueled by a desire to maintain an emotional and aesthetic tie to the past and requires the effort of interested parties, which appear in many forms, including community groups, preservation organizations, and municipalities. Often overlooked, however, is the role developers can play in the revitalization of Main Streets across the country, particularly in the rehabilitation of mixed-use spaces downtown.

As housing increased in the suburbs after the Second World War, we also see the emergence of the suburban corporate landscape in the form of office parks, corporate campuses, and corporate estates. The disintegration of the city as an epicenter for commerce, the rise of suburban housing subdivisions, and the social and economic impact of the new suburban corporate structures provides context for why so many city office buildings have been left deserted. The abandonment of Main Street and the subsequent decay of its landscape have provided a blank canvas for redevelopment.

Developers often carry with them a stigma of destruction, of the heartless big business with only financial interests in mind. As seen in countless movies, developers attempt to demolish culturally significant or historic properties, making way for shiny new shopping centers and luxury condos. The portrayal of developers, as any character in film or literature, is often overblown and fictitious. Although some developers do embody this persona of the greedy corporation whose interests lay only in monetary gain, others seek opportunities to revitalize communities by rehabilitating properties with historic or architectural significance. Many resources exist on the subject of historic preservation from a community or organizational perspective, but the role developers can play in rehabilitation and restoration of older properties has been neglected. In addition to documenting the importance and effectiveness of historic preservation to the civic and economic redevelopment of cities and downtowns, this paper will introduce the role that developers can have in bringing these rehabilitation projects to fruition.

By Aileen Bastos, MA

Building Wellness in the Community

Wellness: the quality or state of being healthy in body and mind, especially as the result of deliberate effort

Reid and Hughes building, currently

The built environment is a physical, (temporarily) permanent representation of our community and ourselves. We live, work, love, and play in buildings and the space between them, and the organization and character of those buildings reflect the culture and values of our society.

The quality of our built environment can be a barometer for the health and wellbeing of our communities, whether they be the city, town, neighborhood, or the street where we live. When a neighbor moves out, the street may lose a bit of vibrancy, life, and activity, all signs of a healthy community. If the house is left vacant over time, the building itself may by physically deteriorating or even falling into disrepair; the same can be seen in a downtown when a business closes and the storefronts are boarded up.

Our work at Crosskey is often focused on repairing or transforming structures that have lost vibrancy, and achieving this effort takes a community of people working together. Architects are partners in performing the work of design and construction, but we require the inspiration of a group of people and their hard work and dedication to give our projects a reason for being.

Change takes a family deciding to open a restaurant in the building downtown. It takes a developer working with local leaders to bring affordable housing to an abandoned mill or factory. It may take a group of citizens contacting their local government about a property falling into disrepair and it takes persistence to obtain funding, support, and approval from agencies and planning boards to create positive, physical changes. All of this and more are part of the process to work towards the physical wellbeing of our built environments, and it can start with something small.

Vision for Reid and Hughes building of the future

Last month, Crosskey employees signed a petition to stop the planned demolition of the Reid and Hughes Building in Downtown Norwich, Connecticut. The building, dating to the 1880s, is listed on the National and State Registers of Historic Places, yet it has been vacant for many years and has fallen into disrepair. There is currently a proposal by the Women’s Institute for Housing and Economic Development to repair and convert the Reid and Hughes building into a mix of commercial space and twenty units of affordable housing, with half designated for formerly homeless veterans. If this plan is allowed to move forward the project could contribute to the health and wellbeing of the community in more ways than one.

Building wellness in our communities takes consistent, deliberate effort and we are happy to be a part of the story of transformation in any way that we can.

By: Erin Marceno, M. Arch

Every Building Needs a Champion

Whether new construction or renovation, every structure needs a champion, specifically, a sustainability champion.

Sustainable buildings are often thought of by developers, owners, and architects, as being more expensive than conventional construction. The standard design approach is, “what can be done with the budget available?” However, once a commitment is made to designing healthy and efficient buildings, the design approach becomes, “how can we honor the natural environment of a particular geographic location while enriching the building occupants?”

By utilizing the natural environmental gifts and assisting the process by introducing renewable energy created on the site, we are able to achieve energy equilibrium at the cost of conventional construction. Commitment is the key component followed by simplicity in construction.

We at Crosskey Architects have embraced the healthy building philosophy, with the use of natural environment; air, water, light and heat in conjunction with the adaptive reuse of man-made structures of past generations.

By Silvana Righenzi, LEED AP, BD + C

A Tale of Two Conferences

An architect and a business development specialist walk into the 2016 Connecticut Housing Coalition Annual Conference. These are their responses to the event.

From the Eyes of an Architect

Often in architecture we hear speeches about how important it is that we provide affordable housing, that entreat us to pat ourselves on the back for the hard work that we’ve done, or how the economy is looking brighter. We don’t always hear (or see) the kind of impact we, as architects, have on the lives of people when we neglect our responsibilities.

Alex Kotlowitzs, Connecticut Housing Coalition Annual Conference keynote speaker, however, chose in his speech last Thursday to uncover the raw issues currently facing not only our state, but our entire nation. His honesty awoke us all from a daze to remind us that our war against poverty, drugs, violence, and homelessness is still very real. As he spoke, the room became quiet and full of guilt; but I like to think that we all left that room motivated to go back to our offices and deal with this problem head on.

Yes, we have made improvements. Yes, we have invested our time and tax dollars. But no, we have not resolved this issue. And it is our responsibility to ensure that our work is focused on healing our communities and providing a safe haven, a place where people want to live, to raise a family, to work, to educate, and most importantly, to create a better future for the next generation.

As Seen by a Business Developer

Housing in Connecticut has been undeniably emphasized and improved during the past five years, as much needed advancement for our state as we work to develop the standard of living for each of our citizens. Today, we stand equipped with excellent homes, both completed and in current construction, for the people of Connecticut to establish their lives within. Our next task seems to be to tackle the social, societal, bureaucratic, political, and environmental challenges that face our residents in achieving the highest quality of living.

Last week’s Annual Conference of the Connecticut Housing Coalition touched on several of these related ripples, including housing availability for an aging population of Connecticut residents no longer in need or desire of large homes, the power of zoning in positively shaping a community, chronic homelessness, housing after incarceration, and many other very real and relevant issues.

Open dialogue and education on subjects such as these is absolutely necessary to make the immense housing development undertaken in Connecticut viable, and empower our communities to thrive. It was both informative and invigorating to join a diverse group, reflective, itself, of Connecticut, to speak about these challenges.

By Michelle Bellucci, LEED Green Associate and Carissa Duhamel

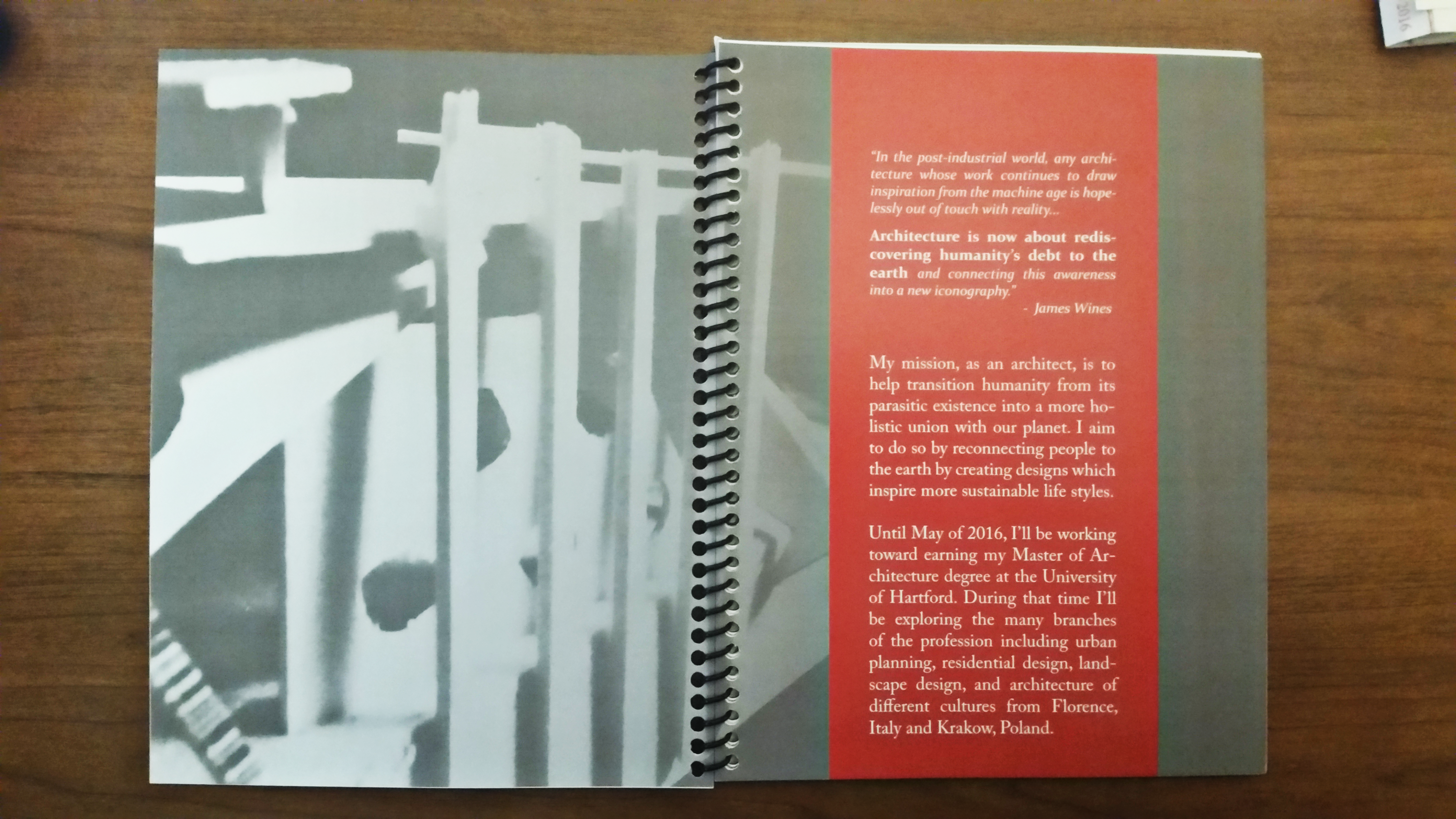

6 Ways to Give Your Life ‘Concept’

As illustrated by Bernard Tschumi, without concept, architecture is just a building. This, of course, is also true with life. Without identity, our lives lack meaning. Has anyone ever asked you, “Why did you choose architecture?” I’m asking you now. Dig deep. Deeper. It’s not because you like to draw. It’s not because you didn’t like engineering. And we’re certainly aware it’s not because of the huge paychecks. Once you challenge yourself to find your life’s concept, the design of it, so to speak, should come more easily. Particularly for young professionals, though it’s helpful at every age, knowing why you want to be an architect will direct you toward your passion. Turn that passion into a job, and that job into a career. When the day comes when you can no longer lift a pencil (or a mouse), you can smile, satisfied in your contribution to the world. Life after graduation can be intimidating, if not terrifying. Follow these six steps to help get you started on giving your life concept.

1. Contemplation and Decision

This probably seems like a no-brainer, but it might take more effort than you expect. Whether you’re a student, or you’re working, life manages to keep us quite busy. It’s necessary to make the conscience effort to sit down with the intention of identifying your passion. Hopefully, over the course of several years of education, this part will come to fruition sooner rather than later. It might take some time, so don’t give up. Grab a sketchbook or notebook and write to yourself, or talk to yourself out loud – however you work best. Here’s a few questions you should consider answering.

- What brings me joy?

- What am I good at?

- Before I began my path to becoming an architect, was there something else I was passionate about? Can I bring that passion into architecture?

- Why did I decide to go to school for architecture?

- Are there any current issues that pique my interest?

- If I could teach someone how to do something, what would it be?

- If money was no object, what would I do with the rest of my life?

2. If you haven’t graduated yet, pick your thesis topic wisely.

Whether it’s your undergraduate thesis, or your M.Arch thesis, this is the perfect opportunity for your to dedicate time to research something that you think you might be passionate about. If it’s helping children learn and grow, you might decide to study how a school can enhance their education. Or perhaps if you’re interested in bringing holistic design to third world countries, you might choose to study how to capitalize on the use of local materials. Use your results from step one to help you decide.

3. Build your brand.

As you solidify what it is you’re passionate about, you can start to build your image around it. This isn’t dissimilar from when we design a project. You start with a concept, and use it to influence your design. While companies use branding as a marketing tool, you can use branding to market yourself when trying to find work. A good place to start is a mission statement. Verbally communicate what it is you’re passion about, and what your mission is. Then you can reinforce it by visually tying together all the components of your package through different graphic styles. This includes your cover letter, resume, business card, portfolio, thank-you letter, and whatever else you include. Unifying all of these elements reads as organized, confident, and prepared.

4. Build your portfolio.

For someone seeking work, this is a very important step. Every interview that I have ever been on has started off with, “Why don’t you walk me through your portfolio?” This is a wonderful blessing if you’re prepared for it, or a nightmare if you’re not. This is where you have the most control because you’re given the opportunity to tell your narrative. Have this in mind when you’re building your portfolio. Think about which projects reinforce your passion and your mission statement, and what order they should go in. This portfolio represents you, and your identity. If something is random or doesn’t quite jive with the story you want to tell, then perhaps it’s best that it’s removed.

5. Go for that dream job. Be passionately aggressive about it.

Don’t be all talk and no action. Know that you have value – find a place that will appreciate that. Use your passion to direct you as to what type of work you want to do, then go forth and own it. All of this thinking and preparing is useless without execution. You might even fail a few times, but not without learning something along the way. There is virtually no penalty for taking big risks here – either you succeed, or you learn and grow.

6. Become both teacher and student.

Don’t ever get comfortable. Stasis is the enemy here. Find new ways to grow and evolve. Use your passion to build yourself an empire that you’re proud to put your name on. Never stop learning, and when given the chance, teach. Pass your passion along to others and let it live on through them. Let your concept be your legacy.

When it comes down to it, the world doesn’t need more architects. The world needs more happy people.

Find your happiness.

Give your life concept.

By Nicholas Fucci